Where is Bobi Wine?

He wears a torn suit, the remains of broken chains are still dangling from his wrists, his tie with the Ugandan flag flutters vigorously in the wind as he stumbles with a determined gaze through a burnt landscape. These were the film posters for “Situka” (“Call for Action”), a Ugandan political love film in which the hero fights for justice.

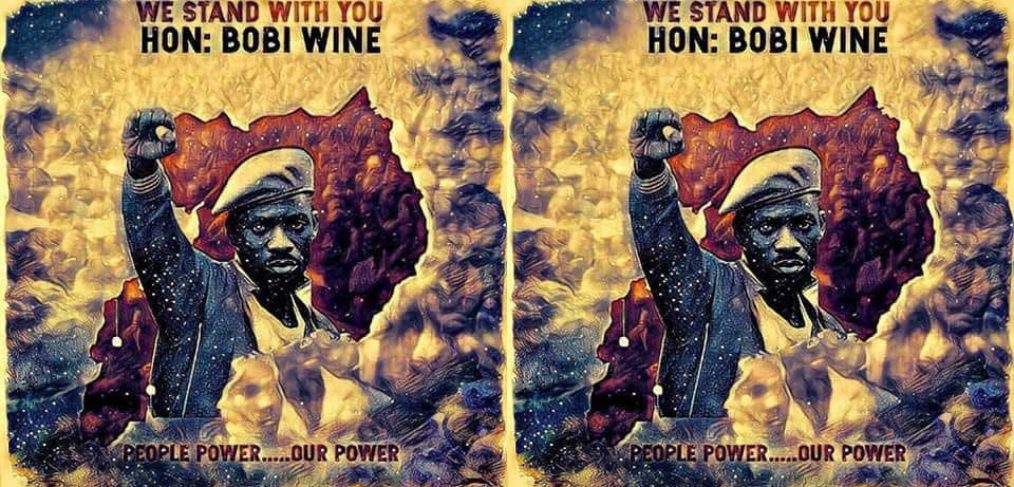

That was 2015, the main actor was the Ugandan musician and actor Bobi Wine, whose civil name is Robert Kyagulanyi. Kyagulanyi was elected to Uganda’s parliament in 2017 during a repeat election in his constituency. Since August 16, 2018 Kyagulanyi has been held in a Ugandan military prison. His wife reports that he is hardly recognizable due to swelling and injuries and can hardly stand on his own.

This too is a story from a Christian African democracy, a country from which hardly any refugees come to Europe, but which on the contrary receives millions of refugees from Southern Sudan itself. Uganda is also the country most densely afflicted by obscure Christian American churches and is one of the most popular destinations for NGOs and development workers.

From liberator to dictator

What happened in less than two years of Kyagulanai’s political career? To understand the events of last year, one has to go a little further: Uganda has been ruled by Yoweri Museveni since 1986. After the dictatorships of Idi Amin and Milton Obote, Museveni was regarded as the leader of the National Resistance Army (NRA) as a great hope for a democratic Uganda. Another leading member of the NRA was Paul Kagame, who later liberated the country as leader of the Front Patriotique Rwandaise after the genocide in Rwanda in 1994 and has been president there since then.

Museveni preached Marxist slogans in his political beginnings, later had liberal approaches, invented a toothpaste made of mutete grass, then showed himself to be a (very) good Christian (in Uganda an above-average number of obscure American spin-offs are anchored in order to proselytize the surroundings from there) and recently attracted attention through increasingly obscure measures. First, he introduced strict laws against homosexuality, which also threaten friends and relatives who do not report gays or lesbians with punishment. The original death sentences have not yet been implemented. Then he had “porn scanners” purchased to detect pornographic images on computers and smartphones, flirted with banning oral sex and finally introduced a social media tax: Anyone using WhatsApp, Twitter, Facebook and Instagram will pay an additional 200 shillings (about 5 cents) a day. How exactly this is to be implemented remains to be seen.

Finally, at the end of 2017, Museveni had a constitutional age limit for presidents removed in order to remain in office longer. Museveni is 74 and thus de facto president for life.

From reality TV star to opposition hero

Robert Kyagulanyi actually had a good career as a musician and actor before he became a Member of Parliament. In the reality show “Ghetto President” he was already something of a politician, with the election he actually became one. And contrary to expectations, he actually took his role seriously – so seriously that it became life-threatening for him.

Numerous mostly peaceful protests developed around the lifting of the age limit at the end of 2017. In more heated debates, however, there was even a brawl in Parliament.

Opponents of the suspension wore red T-shirts or headbands, which over time also became Kyagulanyi’s new trademark. In the course of time, demonstrators were attacked more and more frequently – allegedly by citizens loyal to Museveni. It soon turned out, however, that the attackers were paid thugs recruited mainly from among Boda Bode riders. Boda Bodas are Uganda’s motorcycle taxis, which are an important transport infrastructure and one of the few job prospects for young people. The big organisations that govern this industry sometimes have contacts with crime (read more about Boda Bodas in “The Big Boda Boda Book”). In January 2018, the bosses of a Boda Boda association and high-ranking police officers were arrested in spectacular raids.

All this was fed by a protest movement which Kyagulanyi led until the end and to which several other parliamentarians also belong. As Bobi Wine, Kyagulanyi himself was by no means always a pure democrat. In 2014 he was refused a visa for Great Britain because of his homophonic texts. In 2016 he apologized for this, sought out talks with African LGBTI activists and swore he and his fans would be tolerant.

As a neo-parliamentarian, he first sought contact with liberal MPs, but they found him difficult to trade and continued on his own. At first, the cat-and-mouse play with the establishment also seemed to be part of his staging: Again and again he escaped arrests or police checks, once spectacularly with the Boda Boda, while his car was blocked with tire claws. This provided great pictures, his career as a musician seemed to immunize him against more serious anger. After all, he was already a guest of the Gates Foundation in the USA and thus had protective international attention.

The president has no indulgence

Last week there were new protests in a small town in the course of another by-election. Kyagulanyi was in town to support an opponent, Museveni was also in town to promote his candidate. Stones that damaged the president’s car are said to have flown when the president’s convoy left.

Security forces arrested several demonstrators, including other members of parliament and shot Kyagulanyi’s driver while he was waiting in the car.

Kyagulanyi claimed to have been in his hotel room during all these protests, where he was arrested.

Since then, the story has been somewhat opaque. Kyagulanyi had disappeared for a few days, people feared for his life. Pictures of the other deputies also arrested (Francis Zaake, Gerald Karuhanga, Paul Mwiru and Kassiano Wadri) appeared a few days later, showing signs of abuse. Kyagulanai’s wife, who was able to visit him a few days later, reported a badly maltreated man who was hardly recognizable and could hardly stand on his feet. One day later official places published a photo of Kyagulanai, on which no injuries can be recognized, but his face seems quite deformed.

Will the challengers still win?

Is this another episode of arbitrariness and corruption? It could also be the opposite. Ugandans talk about the events. With his campaign now running for one year, Kyagulanyi has achieved enough reach to attract attention to be able to control his image in public. Journalists, intellectuals and ordinary citizens talk about the events. While older people sound a little resigned, students even give an ultimatum to the government – Kyagulanyi must be released within four days, otherwise Kampala will be covered with demonstrations.

And Kassiano Wadri, the independent candidate whose candidacy has been the cause of the last riots, has won the election.

However, Kyagulanyi must go to court on August 30 as a traitor.